In our digital world, trust is everything. When you visit your bank’s website and see the padlock icon, you’re relying on a system of trust to ensure your connection is secure and you’re not talking to an imposter. This system is built on digital certificates, the cryptographic passports of the internet. But what happens when that trust is broken? And more importantly, how do you verify that trust in a network that is deliberately cut off from the outside world?

This is the peculiar and particular problem of certificate revocation in semi or fully air-gapped networks—a challenge that pits the need for security against the very isolation designed to create it.

The Foundation: Certificates and Revocation

A digital certificate, at its core, is a cryptographic tool used to confirm identity. Issued by a trusted third party known as a Certificate Authority (CA), it binds an entity—like a person or a website—to a pair of cryptographic keys (a public and a private one). When you connect to a website with HTTPS, your browser uses the site’s certificate to verify it is who it says it is.

However, certificates can be compromised. A private key could be stolen, company details might change, or a certificate might be issued fraudulently. In these cases, the CA must invalidate the certificate before its official expiration date. This process is called revocation, and it is a critical signal that a certificate should no longer be trusted.

To check if a certificate has been revoked, clients rely on two primary protocols:

- Certificate Revocation List (CRL): This is the original method, essentially a digitally signed blocklist published by the CA that contains the serial numbers of all the certificates it has revoked. A client must download this entire list and check it to see if a particular certificate is on it.

- Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP): A more modern and efficient alternative, OCSP allows a client to ask a CA’s server (an “OCSP responder”) about the status of a single certificate in real-time. The responder provides a simple “good,” “revoked,” or “unknown” status.

While the industry is moving towards shorter certificate lifespans for websites to reduce the window of opportunity for misuse, the need for revocation remains, especially in one critical area: code signing.

The Compounding Challenge of Code Signing and Timestamping

Code signing is the process of applying a digital signature to a piece of software, like an application or a kernel driver. It serves the same purpose as a certificate for a website: to verify the publisher’s identity and ensure the code hasn’t been tampered with since it was signed.

The stakes here are incredibly high. If a software company’s code-signing certificate is stolen, a malicious actor could sign malware and distribute it as if it were a legitimate product from that company.

This is where timestamping becomes essential. When code is signed, a trusted Time Stamp Authority (TSA) can add a secure timestamp. This timestamp proves that the developer’s certificate was valid at the time of signing. This feature is crucial because software needs to be installable for years, long after the certificate used to sign it has expired. A timestamp allows a system to trust the software indefinitely, as long as the certificate was valid when it was originally signed.

This long time horizon means that robust, long-term certificate revocation checking for signed code isn’t just a nice-to-have; it’s a fundamental security requirement.

The Air-Gap Conundrum: When Security Checks Fail

Now, consider a highly secure, air-gapped network—an industrial control system, a secure research lab, or a critical infrastructure facility. These networks are isolated from the public internet by design to prevent cyber threats.

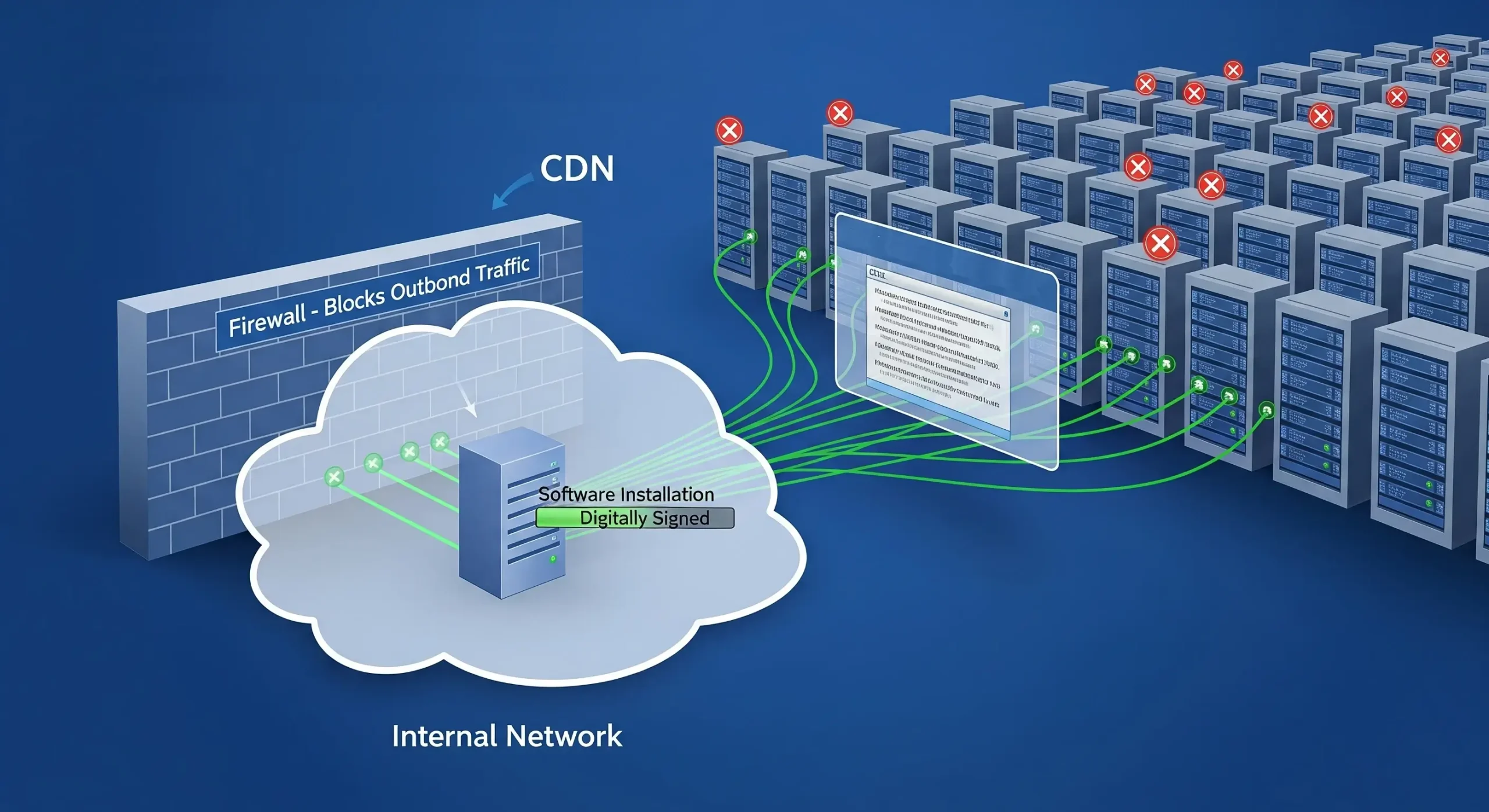

Herein lies the paradox. An operator inside this isolated network needs to install a new, properly signed piece of software. The operating system, in its duty to protect the system, attempts to perform a revocation check by contacting the CRL or OCSP server specified in the certificate. But because the network is air-gapped, that outbound connection is blocked.

The result? The installation process simply hangs, waiting for a response that will never come, or it fails with a generic error. The administrator is left with two terrible options: find a way to bypass the security check, thereby weakening the system’s defenses and opening the door to a potential supply chain attack, or abandon the installation of necessary software.

One might think the solution is to just punch a small hole in the firewall to allow this specific traffic. However, this approach is deeply flawed for two main reasons:

- It Creates a Covert Channel: Any outbound connection, no matter how seemingly benign, can be exploited by malware as a covert channel to exfiltrate data or to connect to a command-and-control server.

- It’s a Logistical Nightmare: CRL and OCSP servers are not hosted on single, static IP addresses. They are spread across massive Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) with a boundless and ever-changing list of IPs and hostnames. Creating and maintaining firewall rules for this is practically impossible.

A Novel Solution for a Vexing Problem

The challenge requires a solution that can allow for this vital security check without compromising the integrity of the air gap. Addressing this, Agilicus has developed a unique approach that acts as a secure, intelligent pinhole for revocation data.

The solution works through a specialised proxy that understands revocation protocols. Machines within the isolated network are configured to send their CRL and OCSP requests to a single, fixed IP address for the Agilicus proxy. The proxy then performs the check on the public internet, but with a critical security layer. It validates all data passing through it in both directions, ensuring that a request is a properly formed and signed revocation check and that the response is a legitimate answer from a trusted authority.

This method effectively bridges the air gap for this one essential function. It allows signed code to be validated securely inside the isolated network while preventing the connection from being hijacked for malicious purposes like data exfiltration. It solves the unbounded IP address problem by funneling all requests through a single point and ensures that the pinhole cannot be used for anything other than its intended purpose.

Strong cryptography is just as vital in isolated networks as it is on the public web. By leveraging an intelligent, protocol-aware proxy, organisations can solve the certificate revocation paradox, ensuring their most secure environments remain both up-to-date and uncompromised.