Why 1 in 4 Operational Technology Environments Got Pwned Last Year (And Why You Are Next)

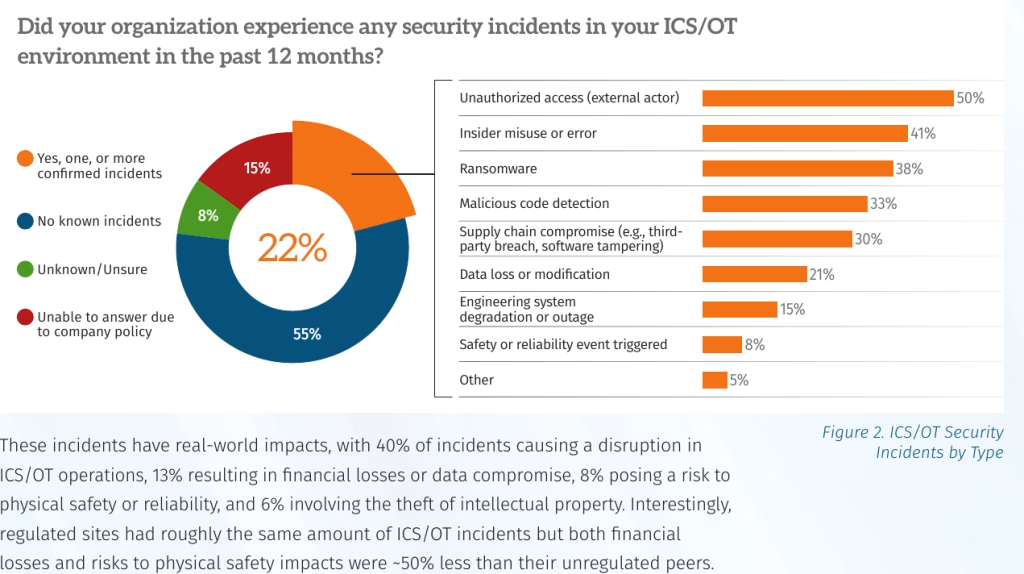

I read the white papers so you don’t have to. It’s a dirty job, but someone has to wade through the acronym soup to find the bones. And folks, the bones in the newly released SANS State of ICS/OT Security 2025 are looking pretty brittle. The headline that made me spill my tea? 22% of respondents suffered a cybersecurity attack in the last 12 months. That is 1 in 4. If it wasn’t you, it was the guy next to you. And for 40% of those, operations actually stopped. We aren’t talking about a defaced website; we are talking about pumps stopping, turbines tripping, and production lines grinding to a halt because that ‘secure’ fortress you built is actually made of plywood.

The One-in-Four Nightmare

Let’s rip the band-aid off, shall we? SANS just released their State of ICS/OT Security 2025 report, and if you were hoping for a pat on the back, you’re in the wrong multiverse. The headline isn’t just bad; it is a statistical indictment of how we build networks. 22% of respondents suffered a cybersecurity attack in the last 12 months.

Read that again. One in four. If you look around a conference table of three peers, one of you is currently putting out a fire. And I don’t mean a theoretical “we blocked a ping” fire. For 40% of these victims, the attack caused actual operational disruption. That means pumps stopped pumping, assembly lines halted, or lights flickered.

When you dig into how these environments got pwned, the data paints a picture of a porous, crumbling perimeter:

- 50% involved unauthorized access by external actors.

- 41% were attributed to insider misuse.

- 30% were a supply chain compromise.

These numbers prove that the “Air Gap” is a myth we tell ourselves to sleep better at night. It is a fairy tale, right up there with “the cheque is in the mail” and “I’ll just change one line of code.” If half of the attacks are coming from the outside, your gap isn’t just bridged; it’s a superhighway. We have connected everything to everything in the name of efficiency, but we are still defending it with architecture from the 1990s when ‘information superhighway’ was futuristic rather than forgotten.

And let’s be blunt about that “insider misuse” statistic. While it sounds like you have a cloak-and-dagger spy in the server room, it is usually far more banal. It’s often a nice way of saying “poor network segmentation.” It is an engineer bridging a connection because the walk to the control room is too long, or a technician plugging in a compromised USB drive because the firewall rules were too annoying to navigate. When you rely on a perimeter defence, once someone is inside — whether it’s a well-meaning employee or a vendor with a compromised laptop — they have the keys to the kingdom. We are building digital Maginot Lines, and the bad actors are just walking around them. The blast radius of a single compromised credential is currently the entire plant floor, and that is a failure of architecture, not just personnel.

The Tootsie Pop Defence is Broken

Let’s talk about candy. Specifically, the Tootsie Pop. You know the one: a hard, crunchy shell on the outside, and a soft, chewy “chocolate” centre on the inside. For decades, this has been the architectural diagram for almost every industrial network I’ve seen. You spend a fortune on a perimeter firewall — the crunchy shell — and assume everything inside is safe.

Here is the cold reality: The Tootsie Pop defence is broken.

The problem with the “crunchy on the outside, soft and chewy on the inside” model is that once a bad actor punches through that outer shell, they don’t just get a foot in the door; they get the run of the entire building. Inside that perimeter, your network is flat, unsegmented, and trusting. It is a playground for lateral movement.

According to the SANS report, remote access remains a top risk, yet only 13% of organisations have fully implemented proper, ICS-aware controls. The other 87%? They are likely using a Virtual Private Network (VPN) and crossing their fingers. We saw the consequences of this with the Cyber Army of Russia targeting US water facilities. They didn’t need a zero-day exploit to manipulate the chemical levels in a water treatment plant; they just walked through open ports and accessed VNC (Virtual Network Computing) sessions that were left exposed. They were clicking buttons on Human-Machine Interfaces while the operators were none the wiser.

This happens because we treat network access as a binary state: you are either outside (blocked) or inside (trusted). This is most obvious when you deal with third-party vendors. You have a technician who needs to update the firmware on a single pump or troubleshoot a specific PLC. So, what do you do? You give them a VPN credential.

This is madness.

Granting full network access via a VPN to fix a single piece of equipment is the equivalent of giving a plumber the combination to your wall safe just because your kitchen sink is leaking. Once that vendor connects via VPN, their laptop — and whatever malware is currently incubating on it — has a direct line to your critical infrastructure.

The VPN is a blunt instrument in a world that requires surgical precision. It connects networks to networks, assuming that valid credentials equal a valid person with good intentions. It is a museum piece. It belongs in a glass display case right next to the floppy disk and the fax machine. If you are still relying on that crunchy firewall shell to save you, you are just waiting for the inevitable crack to appear.

Stop Building Fortresses, Start Checking IDs

If the Tootsie Pop defence is dead — and believe me, the ants are already eating the chewy centre — then we need a totally new architectural model. We need to stop pretending that being “inside” the network makes you a good guy. This is where the SANS report gets real: recovery lags. If you get hit, you aren’t down for an hour; you are likely down for weeks or months. While the report notes that regulation drives maturity, let’s be honest: keeping the lights on and the shareholders off your back is the real driver. You need to survive, and a compliance checklist won’t stop a determined ransomware gang.

We need to shift from network-centric to identity-centric security. As we outline in Zero Trust for Manufacturing Operational Technology, the air gap is a fairy tale we tell junior engineers. We want data, we want remote maintenance, and we want it now. That means connectivity is inevitable. The Agilicus AnyX approach isn’t about blocking that connectivity; it’s about mediating it through identity, not topology. You don’t let a stranger into your house just because they are standing on your porch; so why do you let a laptop access a PLC just because it has a local IP address?

Here is the roadmap to stop building castles and start checking IDs:

- Identity First, Network Second: Stop trusting IPs. An IP address is a coordinate, not a badge of honour. In a Zero Trust model, we treat the local network as if it were the public internet — hostile. We authenticate the user cryptographically before a single packet reaches the asset.

- Precise Authorisation: Connect users to resources, not networks. This is the core of Agilicus AnyX. If a third-party integrator needs to update a specific HMI, they get access to that HMI and nothing else. They don’t get a network drop that lets them scan for vulnerable printers or unpatched servers.

- Kill the VPN: Replace with Identity-Aware Proxies. VPNs are dumb pipes that extend your attack surface to the coffee shop wifi. An Identity-Aware Proxy acts as a chaperone or bouncer, inspecting every request. It creates an outbound-only connection, meaning you have no open inbound ports for Shodan to sniff.

- Multi-factor authentication is non-negotiable: It doesn’t matter if your legacy SCADA system creates passwords that are hard-coded to “admin123”. By placing an identity layer in front of it, you can enforce modern multi-factor authentication on devices that were built when cordless phones meant something very different.

I often hear the pushback that “security hinders operations,” and that operators need instant access without hurdles. That is a false economy, and simply untrue. With Agilicus AnyX and PassKey, its easier to be secure than to not. No passwords to remember. If “ease of access” allows a ransomware gang to brick your control systems, that convenience just cost you the company.

Conclusions

The SANS report makes it clear: the bad actors are getting in, and when they do, the remediation takes weeks. You can keep patching your plywood fortress and hoping the ‘Air Gap’ fairy protects you from the next ransomware campaign. Or, you can adopt a defence-in-depth strategy that assumes the perimeter is already pwned. Secure the identity. Segment the access. Use precise authorisation. It’s not magic, it’s just good engineering. Don’t be the 1 in 4 next year. Check your remote access strategy before someone else checks it for you.